Kissing Spines Susceptibility Risk (KSS)

Gene or Region: BIEC2–668062 and BIEC2–668013

Reference Variant: G

Mutant Variant: A

Research Confidence: Preliminary - Strong Correlation large early study, ongoing research supports the original study

Explanation of Results: KSSR/KSSR = homozygous for Kissing Spines Susceptibility, increased risk KSSR/n = heterozygous for Kissing Spines Susceptibility, moderate risk n/n = no variant detected

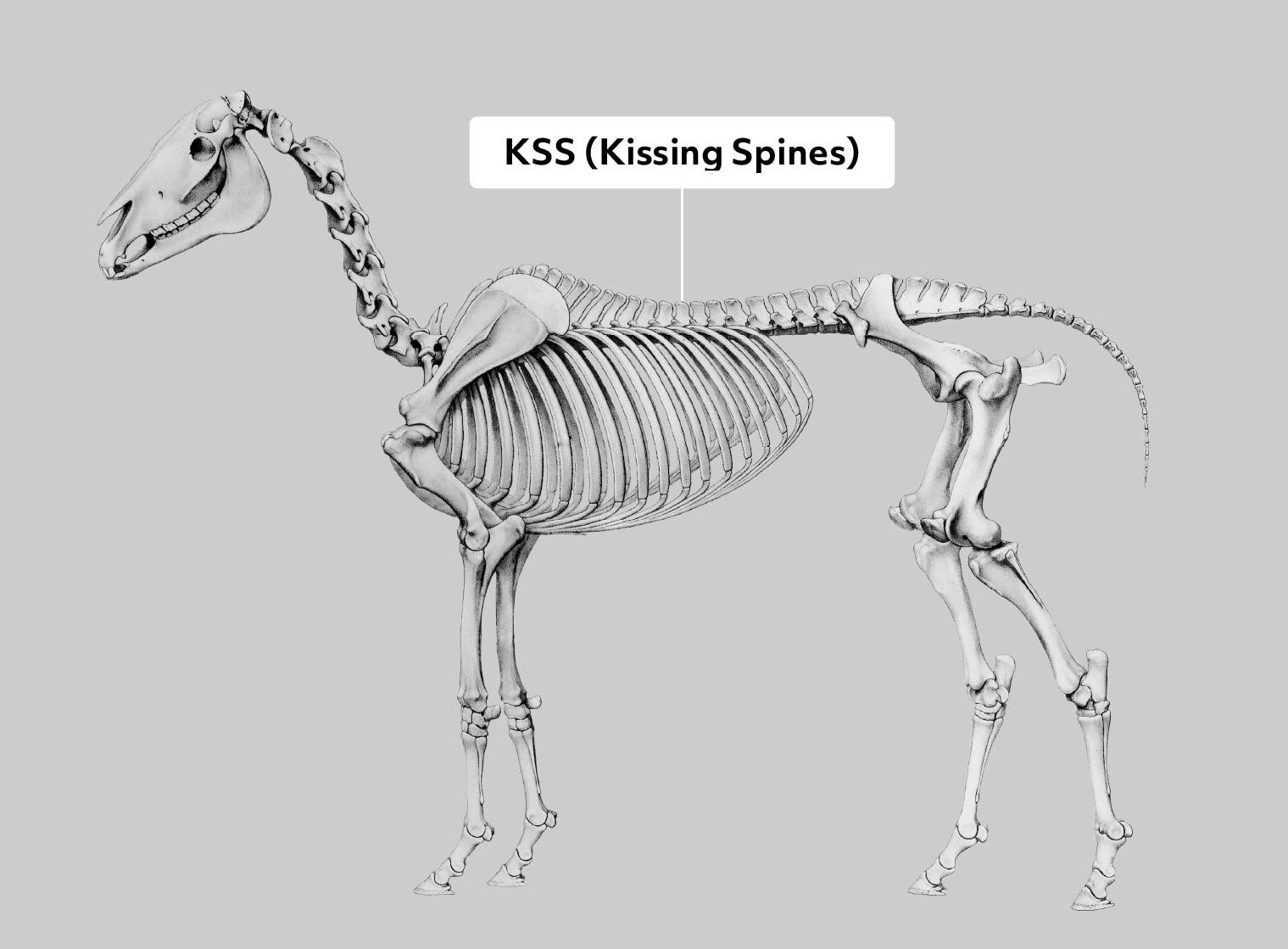

General Description for Kissing Spines

Overriding (or impinging) dorsal spinous processes, better known as “Kissing Spines,” is the lack of space between two or more of the dorsal spinous vertebrae that can cause the horse to have decreased mobility through the spine and experience varying degrees of pain depending on severity. While the disease itself is multifactorial in its development, our research team has proven a link between genetics and the severity of the disease.

Common symptoms of kissing spines include but are not limited to back pain upon palpation, reluctance to be saddled and/or girthed, sensitivity to being brushed, bucking or rearing under saddle, difficulty cantering, and general poor performance. Horses with kissing spines are three times more likely to exhibit back pain compared to an average horse without it.1 Due to the varying degrees of kissing spines, mild cases may show little to no outward symptoms, while more severe cases may cause a horse to exhibit significant pain responses. Diagnosing kissing spines based on symptoms can be deceptive as some horses have evidence of kissing spines on X-rays, yet display no sign of back pain.

Your veterinarian can often diagnose kissing spines based on a combination of your horse’s clinical symptoms and radiographs (X-rays) of the back. Properly angled X-rays allow your vet to assess the distance between the spinous processes and determine if there is evidence of the disease.

What causes kissing spines?

The exact cause of kissing spines has been the subject of debate since it was first identified. It was previously speculated that some horses were genetically prone to kissing spines, and our research has now indicated that may indeed be the case. The Etalon Equine Genetics research team, together with veterinary experts, analyzed radiographs and phenotypic data (observable traits that are determined by genetic makeup and environmental factors such as gender, height, and color) of affected and non-affected horses.2 Each case consisted of independently reviewed kissing spine grades from 155 Warmbloods and Stock-type horses who were diagnosed with kissing spines based on clinical symptoms and X-rays. The horses in the study underwent genetic analysis that compared their genotypes to 50 control horses who were kissing spines negative (validated by veterinarian exam and x-ray).

70,000 locations on the genome were examined, and a region on Chromosome 25 linked to the development of kissing spines was found. A single nucleotide variant (SNV) within this region increased the average grade of kissing spines by one for each copy of the chromosome, called an allele, with the mutation. For each of the horse’s two copies of the allele (one from each parent), the data indicates an average increase in one severity grade of kissing spines thus confirming the link between genetics and the severity of the disease.

While it’s thought that age and sex may also play a role in a horse’s susceptibility to developing kissing spines, our research did not indicate those as being universal risk factors. It does seem, however, that height may potentially have an impact. Biomechanically speaking, as a horse gets taller and body mass increases, there is a disproportionate increase in the forces applied to the spine relative to a smaller horse. Also, the soft tissue structures that support the back, such as the supraspinous and interspinous ligaments, do not increase in strength in a relative manner to the increased size. This may partially explain why there are greater rates of kissing spines in taller horses but this potential link warrants further research.

Kissing spines often occur within the last few thoracic vertebrae (T10-18), which are where a rider and saddle are positioned on the horse’s back. Because of this, there is reason to believe that poor saddle fit, improper training, rider skill, fitness, and weight could all play a role in the development of the disease. These are all examples of non-heritable risk factors that horse owners can be mindful of in the big picture of preventing the development of kissing spines.

Yet, fossil observations of the Equus occidentalis, an extinct horse ancestor that lived prior to evidence of human domestication, demonstrate signs compatible with kissing spines diagnostics.3 This indicates that neither riding nor saddle fitting alone can be solely responsible for kissing spines. The development of kissing spines is likely multifactorial and requires further studies to clarify common components in risk and severity.

It is currently thought that kissing spines is due to some combination of both heritable and non-heritable risk factors. The results of Etalon’s study indicate a genetic component for kissing spines. The benefit of this finding is that horses that carry a genetic risk variant can be identified and subsequently, not used for breeding. Selective breeding can decrease the prevalence of heritable kissing spines in the future.

Kissing Spines Susceptibility Testing

Based on our research, Etalon offers a Kissing Spines Susceptibility Test that can evaluate your horse’s genetic risk for developing kissing spines. Knowing your horse’s risk factor allows you to make informed decisions regarding their riding and breeding careers.

It’s important to note that this test, which identifies a risk variant for kissing spines, is not causative. This means that horses who inherit this genetic variant are not automatically destined to develop kissing spines. This is only one of many factors that are linked to the development of the disease.

What it does mean, however, is that our research suggests that there is a genetic correlation between a risk variant for a higher grade of kissing spines and the development of the disease. This means that a horse who carries the risk variant faces a higher possibility of developing a more severe grade of kissing spines should the condition occur.

Genotype and Phenotype

n/n - Decreased Kissing Spines Susceptibility (KSS) variants detected. Horse has lower risk for developing kissing spines, more likely to fall into the category of grade of 0 (evenly spaced) to 1 (narrowing of the interspinous space).

KSS/n - Moderate Kissing Spines Grade Susceptibility (KSS) variant detected. Horse has moderate risk for developing higher grade kissing spines, more likely to fall into the category of grade of 2 (densification of the margins), and has a 50% chance of passing variant to any offspring.

KSS/KSS - Increased Kissing Spines Grade Susceptibility (KSS) variants detected. Horse has increased risk for developing higher grade kissing spines, more likely to fall into the category of grade of 3 (bone lysis adjacent to the margins) to 4 (severe remodeling), and has a 100% chance of passing variant to any offspring.

Read more about kissing spines here!

- Additional studies with larger equine populations will continue to increase validation into the exact function of this genetic region and the corresponding health of horses. As with any medical test, genetic test, or identification of genetic sequences within your horse, we recommend speaking with your veterinarian regarding any questions you may have about your individual horse’s health or care.

References

Turner, Tracy A,. "Overriding Spinous Processes (“Kissing Spines”) in Horses: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Outcome in 212 Cases." WOUND & ORTHOPEDIC MANAGEMENT AAEP Proceedings 57 (2011)

Patterson Rosa, L., Whitaker, B., Allen, K., Peters, D., Buchanan, B., McClure, S., Honnas, C., Buchanan, C., Martin, K., Lundquist, E., Vierra, M., Foster, G., Brooks, S., & Lafayette, C. (2022). Genomic loci associated with performance limiting equine overriding spinous processes (kissing spines). Research in Veterinary Science, 150, 65-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.06.015

Klide A. M. (1989). Overriding vertebral spinous processes in the extinct horse, Equus occidentalis. American journal of veterinary research, 50(4), 592–593.

More Horse Health

Equine Herpes Virus Type 1 & Induced Myeloencephalopathy

Equine herpesviruses are DNA viruses that are found in most horses all over the world, often without any serious side effects. Following infection of Equine Herpesvirus Type 1 (EHV-1) some horses then suffer Equine Herpesvirus Myeloencephalopathy (EHM), which is is accompanied by serious and sometimes fatal neurological effects. EHM in horses can have serious neurological symptoms on affected horses.

Equine Metabolic Syndrome / Laminitis Risk

Equine Metabolic Syndrome (EMS) is a wide-spread issue in the horse population. Primarily characterized by hyperinsulinemia (excess insulin circulating in the blood in relation to glucose levels), this metabolic disorder is often present in obese horses and ponies and can be challenging to diagnose as it can be misdiagnosed as "Cushing's" (a pituitary disfunction).

Equine Recurrent Uveitis Risk and Severity

Equine Recurrent Uveitis (ERU) is the most common cause of blindness in horses, affecting about 3-15% of the horse population worldwide. Characterized by episodes of inflammation of the middle layer of the eye, Equine Recurrent Uveitis in horses leads to the development of cataracts, glaucoma and eventually complete loss of vision.